Africa's Uncomfortable Choice: Is the Military the "Lesser Evil" in a Failing Democracy?

Introduction

Africa is such a rare incubator. One that is complex, adaptive, and deeply contextual. It is a breeding ground where imported systems often undergo such radical mutation and alterations that their forms become nearly unrecognisable. The contextual sensitivity of the continent has seen few borrowed ideas translate seamlessly on the continent and democracy is no exception.

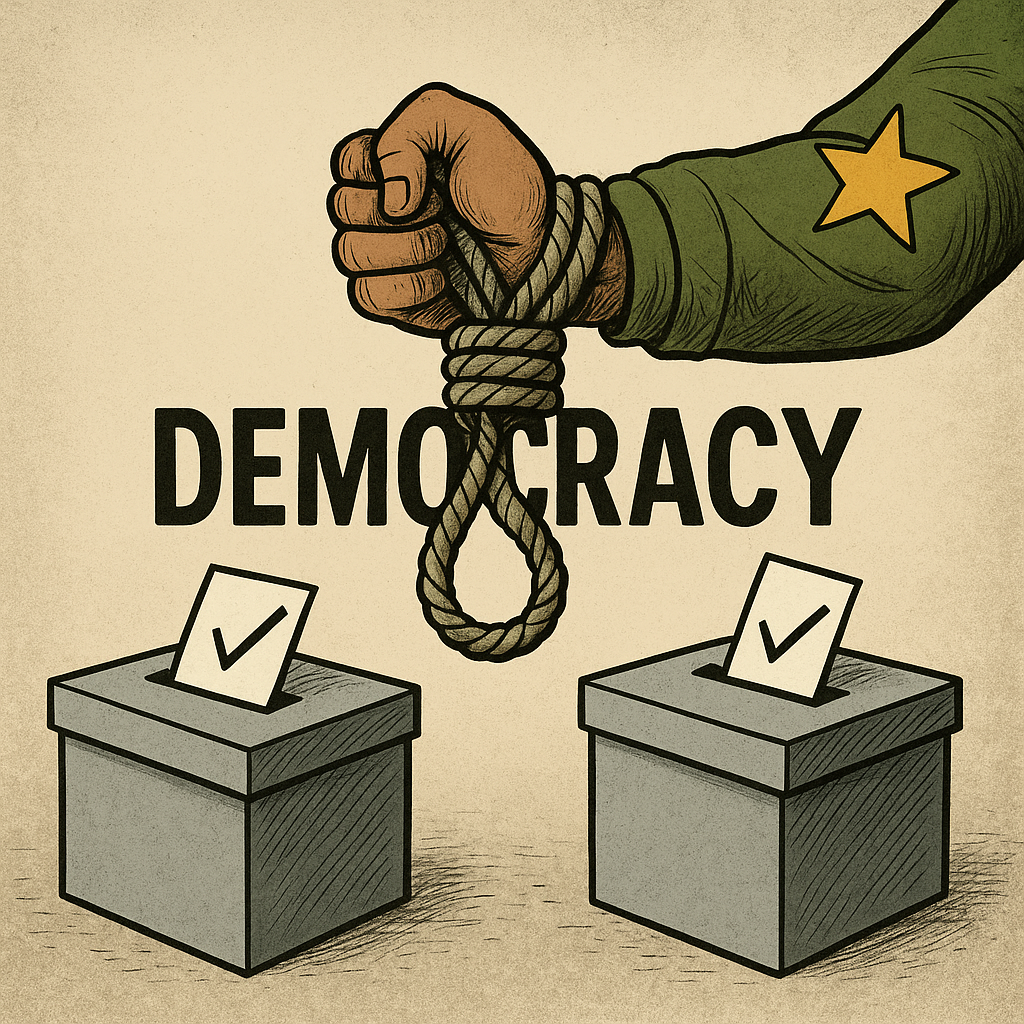

Democracy has long been hailed especially by the west as the “best form of government.” (1) While this has in real sense flourished in most parts of Europe, its transplant into Africa has produced a complicated variant, especially in French West and Central Africa, and the central Sahel region – what some now call a “democratic dictatorship.” How can these two opposing ideas (democracy and dictatorship) coexist within the same regime? Strange, but this breed is extensively present within the governance ecosystem of Africa. Across the continent, democratic governments too often resemble the autocratic ones they replaced – characterised by self-enrichment, corruption, suppression of dissent, electoral malpractices, etc. (2)

Democracy once championed as the golden ticket to accountable governance, prosperity, and citizen empowerment is failing in our very eyes, dishing out a cycle of frustration to African citizens, especially the youth: recurring waves of instability, deepening poverty, rampant corruption, and civil strife have left many Africans, especially a restless younger generation, deeply disappointed. Once considered as a remnant of the past, military takeovers have made an alarming comeback.(3) Just within the past five years, the continent has witnessed nine successful military coups, alongside at least seven additional attempted takeovers. As ballot boxes increasingly deliver processes without tangible progress, critical and unsettling questions arise: when democracy continually betrays citizens’ hopes, is the military the “lesser evil,” or is Africa simply locking itself into a dangerous cycle of old mistakes? Is “the undesirable” actually working for Africa? Is unconventional governance Africa’s necessary evil?

As ballot boxes increasingly deliver processes without tangible progress, critical and unsettling questions arise: when democracy continually betrays citizens’ hopes, is the military the “lesser evil,” or is Africa simply locking itself into a dangerous cycle of old mistakes?

A Crisis of Faith: Declining Support for Democracy

The continent has not just seen a rise in coups; it has also experienced a slight decline in popular support for democracy and a notable increase in the support for military takeovers.(4) Increasingly, the question if military regimes are the lesser evil is not rhetorical. It is being answered in reality by growing public support for military governments in several countries. The recent waves of Afrobarometer surveys reveal that although a majority of Africans still express support for democracy, its support is declining, while willingness to consider military intervention is rising especially when civilian leaders are seen to abuse power. Countries with recent coups have seen very sharp declines. In Burkina Faso, support for democracy plummeted from 70.3% in 2021 to 55% in 2023; in Mali, it fell from 62% to only 38.6% over the same period. This downward declining support for democracy is visible not only in countries where a coup has taken place in the past four years. In Cameroon for example, support for democracy slipped from 62% in 2018 to just 50.4% in 2025 – almost a 50/50 split for the first time. The story is not very different even in “democratic strongholds.” In Ghana for example, support for democracy fell from 81% in 2018 to 75.9% in 2023. In Kenya, the drop was from 77.7% in 2023 to 74% in 2025. (5)

Recent Afrobarometer surveys reveal a striking increase in popular support for military involvement in governance across many African countries—not only those that have experienced recent coups with support rising from 20% in 2021 to 26% in 2023 and 27% in 2025 across the continent. This trend is particularly pronounced in countries that have experienced recent coups, such as Mali, where over 77% of the population supported or strongly supported military takeover in 2023 (up from just 16% in 2021), and Burkina Faso, with over 65% supporting military rule (up from 21% in 2018 and 50% in 2021).(6) Importantly, this trend is not confined to coup-affected nations; even in countries like Kenya, support for military rule has risen from 9% in 2021 to over 30% in 2025, demonstrating a broader relaxation of positions towards military intervention even where support remains comparatively low. This indicates a continent-wide re-evaluation of governance models, driven by the perceived failures of established democracies. Even in countries where overall support for military rule remains low, the population is seen relaxing its strong opposition. In Kenya, for example, among the over 80% of the population who disagreed with military rule in 2021, 75% strongly disagreed. (7) By 2025, though the percentage of those who disagreed reduced to 70%, the number of those who strongly disagreed fell to 59%, while those who just disagreed rose to 21%. Similarly, in South Africa, among the 64% who disagreed with the idea in 2021, 42% strongly disagreed; by 2023, this number fell to 53% disagreeing, with only 27% strongly disagreeing, and 14% remaining undecided. (8)

The case of Ibrahim Traoré exemplifies this shift. For some, he embodies a bold break from the failures of “imported” democracy. While his critics are decrying a dangerous step backward, his supporters are hailing a leader who has finally stood up to elites, terrorists, and and imperialists. The Institute for Security Studies’ African Futures and Innovation projects that Burkina Faso could see its economy grow by an average of 8% annually from 2025 to 2043. His popularity has soared, not only locally within Burkina Faso but also across the continent and within the diaspora, especially following incidents like the widely publicized outing of General Michael Langley. This tells us that the concerns driving such support are not unique to Burkina Faso; indeed, young Africans often express themselves as though Traoré is not merely a voice for the Burkinabé people, but a resonant voice for Africans generally, signalling a deep, continent-wide yearning for leaders who prioritize genuine impact. Traoré’s ascent raises urgent questions however: is this outsized support a fleeting reaction to failed democracies, or does it signal a genuine appetite for a new, unapologetic brand of African leadership? Are we looking for the “man” Africa needs, or the institution Africa needs? For sure the institutions are more important than the “man”. Yet, can we get these institutions without a “man”?

As ballot boxes increasingly deliver processes without tangible progress, critical and unsettling questions arise: when democracy continually betrays citizens’ hopes, is the military the “lesser evil,” or is Africa simply locking itself into a dangerous cycle of old mistakes?

People Want Results, Not Labels

Is this piece an endorsement of military takeovers? No. Far from that. Military regimes are not without their dangers. Historically, they have been associated with crackdowns on dissent, media censorship, and long-term stagnation. Military rulers often arrive promising order, only to entrench themselves and replicate the very dysfunction they claim to oppose. In its present and during crises, , the “lesser evil” narrative looks and is considered as a legitimate necessity which increasingly citizens are willing to pursue irrespective of the full knowledge of its potential consequences. This therefore tells us that the conversation is not about rejecting democracy or embracing military rule or other alternative unconventional forms of governance. It is about the everyday decisions young people make when survival is on the line. For someone in a conflict zone or under economic stress, governance is measured not by procedure but by impact. The “lesser evil” only becomes a necessary topic of discussion when the “supposed good” is not truly working. We must therefore be careful not to scrutinise the lesser evil without being so critical of the supposed good. Failure to do this, Africa risks becoming stuck in a cycle, choosing the “lesser evil” simply because the supposed good has never truly worked. Broken democracies open the door to military regimes, which eventually fail or overreach, leading back to civilian governments that disappoint again – the cycle we must break out from.

Africa’s predicament is not just a stark choice between ballots and bullets—between democracy and military rule. It’s about the profound gap between the system that citizens were promised and the one they’ve received. The resurgence of military interventions is not a sudden embrace of authoritarianism, but a symptom of deep-seated disappointment. Africans are gradually moving past mere subscription to a particular form of government. The form – civilian or military is secondary to their cravings. Africans are looking for what actually works, not just what sounds right on paper. – they want security, functioning infrastructure, jobs, and justice. If democratic institutions are unable to provide these, citizens will continue to look elsewhere, including to the armed forces.

As ballot boxes increasingly deliver processes without tangible progress, critical and unsettling questions arise: when democracy continually betrays citizens’ hopes, is the military the “lesser evil,” or is Africa simply locking itself into a dangerous cycle of old mistakes?

Conclusion

Does this mean African democracy was doomed from the start? Not necessarily. The issue is less about the imported ideals of democracy and more about weak, unaccountable institutions. Democracy, if it is to thrive, needs more than ballots—it needs effective checks and balances, rule of law, and political cultures focused on the collective good rather than individual or ethnic spoils. Too often, it seems our understanding of democracy focuses solely on preventing the rise of overtly authoritarian rulers—leaders who seize absolute power and silence dissent. But this narrow perspective can obscure subtler, yet equally damaging, undemocratic tendencies that take root under the guise of democratic rule. By fixating on the threat of dictatorship, societies may overlook how elected leaders and interest groups quietly subvert democratic norms, manipulating laws or institutions for personal or partisan gain. True tyranny is not limited to an individual dictator; it can emerge wherever people in power, whether a single leader or an elite group, exploit their position to extract unearned social or political advantages. Such abuses, cloaked in the legitimacy of the ballot box, often go unnoticed until they have caused as much harm as, or sometimes more than, the clear-cut excesses of authoritarian regimes. In this sense, democracy’s greatest challenge is not just defending against dictatorships, but rooting out the many forms of tyranny that can flourish under the cover of democracy itself.